Car-centricity as a Hyperobject

How using the Hyperobject framework can help us fight the war on cars.

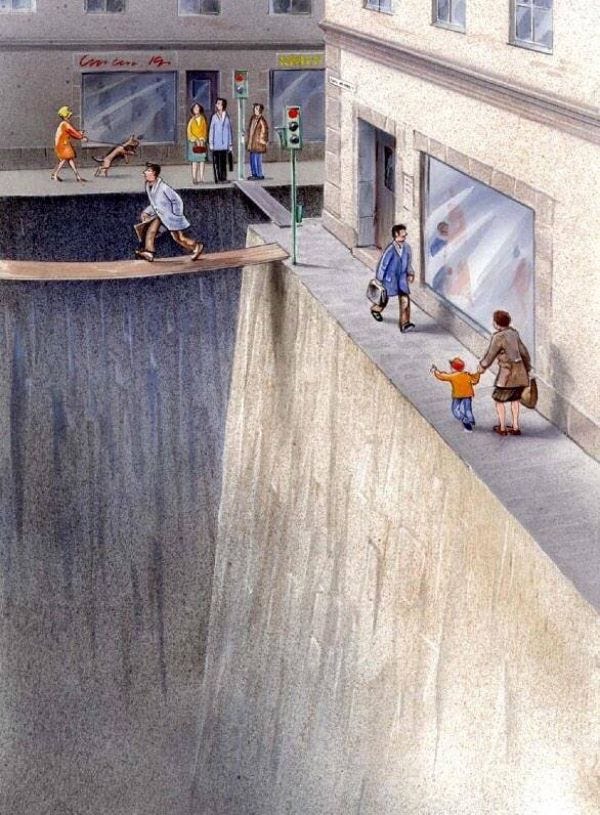

“When was the last day you went without seeing a car?” It is a simple thought exercise, but one that once you take the time to ponder the answer, will lead you to realize just how omnipresent cars and car infrastructure are in our daily lives. When I asked myself that question, on a walk around the neighborhood of my childhood home in Sterling Heights, Michigan - a prime example of car-centric suburbia found all over the United States, it was the first time I confronted the issue of car-centricity in the United States. Answers are much easier to find for other forms of transportation. When was the last day you went without seeing a train? How about a plane? A bus? This is just one example of how cars and car infrastructure have become so pervasive in modern society that we cannot see outside this built-environment framework. When was the last time you existed in a space designated for cars outside of a vehicle? Did it make you uncomfortable? For example, walking in the middle of the street. Did it feel unnatural? We have been conditioned to leave an unfathomable amount of space for automobile transportation and leave the scraps for other forms of existence.

Have you ever wondered what built forms existed before the implementation of car infrastructure? There is an extensive collection of photos that show the change in the urban landscape wrought about by the development of the Interstate Highway system. But the changes in the built form go much deeper than that. What buildings existed prior to the construction of that parking garage? What about what occupied the space now allotted for on-street parking? What vibrant ecosystem was present before being bulldozed to provide space for a parking lot? All of these questions are very difficult to wrap your head around because of how intense and omnipresent the development of car infrastructure has been since the proliferation of the car in the early 20th century. The almost complete consumption of the built environment by the automobile makes it feel as though that is how it has always been. The automobile and the infrastructure it requires have transcended into a plane of perpetual existence, always affecting how we interact with the world even if it is not directly present. The car has reached the status of a hyperobject. A concept developed by philosopher Timothy Morton, a hyperobject is defined as something so “massively distributed in time and space” that they are often imperceptible to the human experience. One may be able to perceive a snapshot of the hyperobject, but it is too large to ever be captured in its entirety. Other examples that Morton identifies are climate change and global plastic pollution. I contend that car-centricity is another hyperobject that must be reckoned with.

Morton lists several criteria for something to be considered a hyperobject, they are:

1) Viscous: The hyperobject is everywhere, like fog. Car infrastructure has become so normalized in modern society that it is notable when it is not apparent. This omnipresence has become so entrenched that we are self-aware of its overbearing existence. This has become an online meme when posting a scene without car infrastructure present.

2) Nonlocal: Car infrastructure and car-centricity are distributed across the world. While some countries are doing better than others in transitioning away from car dependence, the car is the default mode of transportation in almost every society, especially developed ones. The effects of car dependence also go far beyond the changes it makes to humanity’s built environment. The carbon emitted from automobiles will have lasting effects on the earth’s climate. The particle pollution from the billions of used car tires has spread around the world, reaching areas that cars themselves cannot reach.

3) Temporal Undulation: A hyperobject’s lifespan is measured in planetary time, not a human timeframe. Car-centricity is one core aspect of the birth of a new geologic age: the Anthropocene. This geologic age is different from previous ones because of the impact humanity has had on the Earth’s systems. Our ability to harness huge amounts of energy to sustain an incredibly inefficient mass transportation system of car-centricity will have effects on human society that far outlive our own lives.

4) Phasing: Hyperobjects are so large that a person can only see a ‘phase’ of a hyperobject. No one alive today was around to experience the rapid proliferation of the car and the birth of international car companies which coincided with the destruction of public transportation in North America and the complete transformation of urban landscapes. No one alive today will live to see the end of car-centricity on a global scale. We can fight for wins on local, city, state, or even national scales. However, the hyperobject of car-centricity is too large of a physical force and cultural phenomenon for any one generation to end on its own.

5) Interobjectivity: A hyperobject cannot be described by a single object or phenomenon, it is present in a multitude of manners whether it is physical, cultural, or scientific. You could point to a highway as an example of car-centricity, but car-centricity will still exist with or without that highway, or every highway in a nation. Car-centricity exists in an almost infinite amount of variations that cannot be expressed in one essay. The effect of all these manifestations of car-centricity is what creates the hyperobject of car-centricity itself.

The detrimental effects car-centricity has on our society have been written about many times over. However, if we utilize the hyperobject framework, it allows us to put the problem into perspective. A hyperobject narrative provides us with a story to effectively combat the issues of car-centricity. No one alive today was around to experience the birth of car-centricity, and no one alive today will see the complete end of car dependency. It is a hyperobject too large for a single person to experience in full. In a sense, it is comforting to know that we will not see the end of car-centricity, it is too large a problem for one generation to solve on its own. Instead, we must see ourselves as a stage on the journey toward the end of the hyperobject’s existence. The advocacy, research, and work we do today will help put future generations in a better position to improve the built environment and reduce the harmful consequences of car-centricity. For those invested in the war on cars, a future where cars are no longer the primary method of transportation is a future worth fighting for, no matter how far in the future it is.